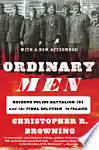

Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland

Christopher R. Browning

Harper Collins, 2017 (Revised Edition)

xxii + 349 pages

Men kill for many reasons: revenge, hatred, envy, self-defence, patriotism, love. Professor Browning, after a fortuitous find of documents in Ludwigsburg, reconstructs the history of Reserve Police Battalion 101 and makes a compelling case for another reason men kill. The reason is depressing.

For students of history who are unaware of just how difficult it is working with primary sources, I strongly urge you not to skip the preface. The bulk of Browning’s study comes from the judicial interrogations of 125 men conducted in the 1960s. Although a treasure trove of information, he reviews the problems he faced with these sources: they were an incomplete catalogue of the battalion members, some of the subjects interrogated had faulty memories and above all some of them lied, as “they feared the judicial consequences of telling the truth as they remembered it.” (p. xviii) Despite these problems, Browning, through careful use of the interrogations and cross-referencing with other sources, has skilfully reconstructed much of the history of Reserve Police Battalion 101.

Since the book’s purpose is to figure out why these men committed genocide. Browning devotes time explaining where the reserve police battalions fitted into the German military. They were a mix of career police officers and older army reservists whose main function was to police conquered civilian populations in Poland and the USSR. Several battalions, however, worked alongside the Einsatzgruppen in massacring Jews and other undesirables in the wake of Operation Barbarossa. What of Police Battalion 101? Who were they and what were they doing? Most were from Hamburg. In the early stages of the war, they carried out the “resettlement” of thousands of Poles and guarded the Lodz ghetto in the spring of 1940. After a spell back in Hamburg, with a major reorganisation, an influx of new reservists and extensive training, the battalion helped round up Hamburg’s Jews for deportation and “resettlement” in the east. By the summer of 1942, the battalion was back in Poland. It was, in a sense, a new battalion due to the reorganisation mentioned above. Who were these new men? About twenty-five percent were NSDAP members. Yet, most were working-class from one of the least Nazified cities in Germany. Summing up this group, Browning states

The men of Reserve Police Battalion 101 were from the lower orders of German society. They had experienced neither social nor geographic mobility. Very few were economically independent…Presumably a not insignificant number must have been [communists and socialists] given their social origins. By virtue of their age, of course, all went through their formative period in the pre-Nazi era. These were men who had known political standards and moral norms other than those of the Nazis. Most came from Hamburg, by reputation one of the least nazified cities in Germany, and the majority came from a social class that had been anti-Nazi in its political culture. These men would not seem to have been a very promising group from which to recruit mass murderers on behalf of the Nazi vision of a racial utopia free of Jews. (p. 48)

And yet killers most of them became. For one hundred pages, Browning catalogues the deportations, summary murders, massacres and “Jew hunts.” In their first massacre, the battalion killed around 1500 Jews at Józefów using the “neck shot”. Another 1,700 were killed at Lomazy with the help of Ukrainian volunteers, the so-called Hiwis. Other massacres followed along with more deportations. By November 1942, Reserve Police Battalion 101 “had participated in the outright execution of at least 6,500 Polish Jews and the deportation of at least 42,0000 more to the gas chambers of Treblinka.” (p. 121)

Worse was to come. Some Jews had escaped the Nazi dragnets and gone into hiding. In Lublin district, the battalion carried out its first Judenjagd (Jew hunt) at Parczew forest in November 1942. One member of Reserve Police Battalion 101 provided a vivid description of this sweep:

“We were told that there were many Jews hiding in the forest. We therefore searched through the woods in a skirmish line but could find nothing, because the Jews were obviously well hidden. We combed the woods a second time. Only then could we discover individual chimney pipes sticking out of the earth. We discovered that Jews had hidden themselves in underground bunkers here. They were hauled out, with resistance in only one bunker. Some of the comrades climbed down into this bunker and hauled the Jews out. The Jews [some fifty] were then shot on the spot…including men and women of all ages, because entire families had hidden themselves there.” (p. 124)

Smaller patrols searched forests to pick off individual bunkers of still hiding Jews who escaped larger sweeps. Where did the battalion get its information on these hiding places? A network of Polish trackers. More depressingly, many Poles simply volunteered information to rid themselves of the nuisance of starving Jews stealing grain and food.

So why did Reserve Police Battalion 101 commit these atrocities? Those who know only the cartoon version of Hitler’s regime guess that to not follow orders meant the concentration camp or worse. Not so. Indeed, just before the massacre at Józefów, Reserve Police Battalion 101’s commanding officer, Major Wilhelm Trapp, gathered his men and told them that their job was to round up the Jews, march working-aged men to a slave-labour camp and shoot everyone else (including infants). After explaining their task, “Trapp made an extraordinary offer: if any of the older men among them did not feel up to the task that lay before them, he could step out.” (p. 2) A dozen men of the 500 gathered round Trapp stepped out. The rest continued with the massacre.

There were no harsh punishments for refusing to kill. In fact, Browning tells us of men asking for reassignment from killing; Trapp and other officers typically granted these requests. And yet, the vast majority did as told. Again, if it was not fear of punishment or Nazi racial zeal, what was it? Browning spends the last thirty pages of his book trying to figure this out. After eliminating several reasons (e.g., a radical commitment to National Socialist values), he concludes that these willing executioners’ actions were multicausal. Relentless propaganda and indoctrination played a role especially with younger members of the battalion. Group conformity was another cause:

The battalion had orders to kill Jews, but each individual did not. Yet 80 to 90 percent of the men proceeded to kill, though almost all of them—at least initially—were horrified and disgusted by what they were doing. To break ranks and step out, to adopt overtly nonconformist behavior, was simply beyond most of the men. It was easier for them to shoot.

Yet for Browning, the crucial factor was ingrained obedience to authority. The author draws heavily on Stanley Milgram’s experiments from the early 1960s which concluded that “as a product of socialization and evolution, a “deeply ingrained behaviour tendency” to comply with the directives of those positioned hierarchically above, even to the point of performing repugnant actions in violation of “universally accepted” moral norms.” (p. 172) Milgram demonstrated that most humans, even with the absence of coercion, will follow immoral orders if they recognise the person giving the command as a legitimate authority. Of course, the actions of Reserve Police Battalion 101 do not parallel a university experiment; however, Browning makes a strong case that “many of Milgram’s insights find graphic confirmation in the behaviour and testimony of the men of Reserve Police Battalion 101.” (p. 174)

Browning’s conclusion brings us back to the beginning of this review. The Nazi state did not threaten these murderers with death or the concentration camp for non-compliance. Most were not hard-core Nazis. No, they were ordinary men who killed because it was easier to follow authority than to exercise personal moral responsibility. They were only following the orders they recognised as legitimate. How disheartening! It is, moreover, a timely story for us today. The twenty-first century is littered with examples of humanity blindly following orders.